by Gerry Dawes

For fans of Spanish wines, and particularly those crafted from tempranillo - Spain's finest indigenous red wine grape - the 2001 harvest may have produced one of the greatest vintages of all time - an ironic conclusion to a rollercoaster growing season afflicted by hard frost, inordinate heat, prolonged drought and potentially damaging rains.

On back-to-back visits in September and October, I spent more than six weeks prowling the vineyards of Spain's key red wine-producing regions - from the firmly established La Rioja, Ribera del Duero, Navarra, Penedès and Priorato to up-and-coming spots such as Toro and La Mancha. A veteran of more than a dozen Spanish harvests, I have rarely seen grapes in such healthy condition or a harvest season (vendimia) that enjoyed such propitious weather.

In their reports on the 2001 vendimia, most of Spain's preeminent winemakers concur. In the top red-wine regions, many are using such superlatives as magnífico, espectacular, extraordinario and una cosecha para la historia (a harvest of historic quality) to describe the 2001 vintage. In those early reports, they expressed confidence that the resulting wines will have great depth of color, superb aromatics and concentrated flavors. The best of them were already showing "silky tannins" that will make them drinkable young, but still auger well for long-term cellaring.

Some producers in La Rioja, where tempranillo is the main grape, predicted the 2001 vintage for red wines would be superior even to the exceptional 1994 vintage. A few even ventured that last year's wines might be the best since 1964 (considered by most experts to be the standout vintage of the 20th century in La Rioja).

All was not so rosy, however, earlier in the year. Rather, prospects looked downright grim. In April, hard frosts and "black ice" (caused by freezing mist, thin coatings of ice covered the vines) wiped out 20 to 60 percent of the expected crop in many major wine regions. In the Ribera del Duero, José Manuel Pérez, the Pérez Pascuas family's enologist at Viña Pedrosa, says his crop was only about 40 percent of normal quantity.

Summer brought near-drought conditions to many regions. Miguel Torres, president and technical director of Bodegas Torres, reports his crop was down 25 to 30 percent in Penedès and in Cataluña in general. South of Penedès in Priorato, an area accustomed to dry years (and resulting wines with high alcohol levels), Carles Pastrana of Costers de Siurana, producers of Clos de L'Obac, says summer was inordinately arid, even by Priorato standards. Alvaro Palacios, owner-winemaker of Bodegas Alvaro Palacios, says the early summer dry spell, in tandem with prolonged heat, caused yields to plummet to 50 to 70 percent of normal.

Then, in late summer, torrential rainstorms hit places such as La Rioja, prompting Bodegas Muga owner Isaac Muga to use some salty expletives to describe the gully-washer that had struck his particularly fine-looking stands of grapes. At first, many winegrowers, such as Muga and his son, Jorge, thought the tardy rains would swell the water-starved grapes, only to be followed by more rains ruining what was already going to be a short crop. The September storms broke the drought (a few regions got a little precipitation in August, too).

As it turned out, the rains gave way to classic autumn weather, and the grapes ripened under nearly perfect conditions in most of Spain's key wine regions.

Many growers, though disappointed with their lower yields, were compensated by the superiority of their red grapes. Shortly after the harvest in Cataluña, Miguel Torres observed: "In terms of quality, the result has been excellent with extremely healthy grapes possessing a great wealth of sugars, aromas and tannins." Within a few months, Torres reconfirmed his earlier assessment: "The wines of 2001 are excellent, particularly the reds." Although he is more famous for his cabernet sauvignon-based wines, such as Gran Coronas (Black Label), his Merlots and his Grans Muralles (a blend of four recovered Catalan varietals), he also grows tempranillo, generally using it as a blending agent. "The standout red wines this year are my Tempranillos," he reports. "They are probably the best we have tasted in the past ten years, yet the Merlots and Cabernet Sauvignons are also among the best of the past decade." Torres also predicts great things for his Grans Muralles blend (it hails from an estate in the Conca de Barberá denominación de origen). "The colors are very intense, and it is full and rich in the mouth with an exquisite density of flavor that presages a great future for this wine," Torres says. He also vinified 5.5 tons of fruit from the first harvest of his new vineyard in Priorato. "Despite the fact that the vines are so young, in 2001 we got intense fruit and magnificent structure," he says.

Trailblazing Priorato winemaker Alvaro Palacios, one of Spain's brightest young wine stars, is acquainted with the 2001 vintage from a three-point perspective: In addition to making wine at his eponymous Priorato winery, he oversees with his brother Rafael their family winemaking operations at Bodegas Palacios Remondo in La Rioja Baja and, with a cousin, he makes wines from a spectacular old-vines mencia (a grape related to cabernet franc) vineyard in Bierzo (an up-and-coming DO in northern Spain's León province). "The potential in all three of the regions is great," he observed in December. "My Priorato wines [which include the stellar old-vines L'Ermita Vineyard] will be unusually potent and concentrated. The sporadic September rains served to stabilize the sugar levels and give the wines more acidity to balance the richness." He expects an excellent wine from L'Ermita in 2001.

Carles Pastrana of Costers de Siurana, producer of Clos de L'Obac, says his 2001 Priorato wines have "fantastic concentration." Pastrana, who makes some of the longest-lived wines in the region - his 1998, 1999 and 2000 wines are remarkable - harvests Priorato's native garnacha and cariñena grapes before they reach the overripe levels that many wine critics seem to prize these days. He noted that while the normal harvest period lasts 40 to 45 days, because of the heat and dry weather in 2001, Clos de L'Obac's harvest was completed in just twelve days.

In the Ribera del Duero, at the Pérez Pascuas family's Viña Pedrosa, their high-altitude estate in the Ribera de Burgos region, yields were about 225 gallons of wine per acre. Shortly after the harvest, Pedrosa enologist José Manuel Pérez predicted that 2001 would be one of the greatest vintages of all time in the Ribera del Duero. Interviewed again in February, he remained true to his earlier assessment. "The evolution of these wines in barrel has been magnificent; they are perfectly balanced and show enormous potential as wines for laying down. We are still talking about a year that can be defined as being among the greatest of the Ribera del Duero's great vintages," Pérez confirms.

In the warmer western zones of the Duero Valley, Bodegas Mauro's Mariano García, the man many believe to be Spain's greatest winemaker, is slightly more circumspect. "Two-thousand-one has been an excellent year in the greater part of the Spanish geography," observes García, who also owns Maurodos in Toro and consults at a handful of bodegas in his Castilla-León region and in La Rioja. "It was a short crop, but it has given ripe, very concentrated, deeply colored wines. In the Ribera del Duero and in my Tudela vineyards, 2001 can be compared to 1999 for the quality of its fruit tannins. The wines will be very fruity and should age well."

Florian Miquel Hermann, a wine writer for El Mundo, one of Spain's top newspapers, is cautiously optimistic about the 2001 wines of the western Duero Valley. "There is indeed a lot of euphoria concerning the 2001 Ribera vintage," he says. "I've tasted little so far - only at Mauro, Leda, Aalto (all made by García's hand) and Abadia Retuerta, another non-DO wine from this region - but based on this limited sampling, I found much to like. On the other hand, I strongly believe that it's too soon to judge whether 2001 qualifies as a truly 'historic' vintage.

"We shouldn't forget," Miquel Hermann continues, "that there are many microclimates in the Ribera Valley and that there was hail and frost just after flowering. Therefore, the growers got significant percentages of second generation fruit," he explains. "Obviously, everybody claims that he has eliminated these bunches, but knowing the mentality of the viticultores, I can only smile. All that said, polyphenol levels [phenolics are the myriad organic building blocks in wine that account for color, tannin and flavor attributes] seem to be very high everywhere," adds Hermann, who remains on the fence.

Hermann is not alone. By late February, Spain's famous Vega Sicilia, located at the western end of the Ribera del Duero, had announced it would not make a 2001 Unico, the wine it produces only in what it recognizes as exceptional years. Those who follow Vega Sicilia, however, understand this is not necessarily a warning that the vintage was not great elsewhere. For example, Vega Sicilia's reserve vintages have been an anomaly on many occasions, making Unico in such years as 1974 and 1987 - vintages that were not considered outstanding years by other wineries in the region.

According to Winemaker Xavier Ausas, the hard freeze that hit Vega Sicilia's vineyards in the spring wiped out a large percentage of the crop: "A second flowering of the vines followed, but it produced fruit that lacked the characteristics required for our top-of-the-line Unico, which can spend from 15 to 25 years aging in our cellars." Instead, the grapes that he deemed of "good quality" were destined for the Valbuena and Alión wines.

In contrast, west of the Ribera del Duero, in Toro, Mariano García again had much for which to be thankful. "The crop was 50 percent of normal, but we have some very opulent, tannic wines," he reports. "The key is the fact that we have achieved elegance and balance."

In Navarra at Bodegas Julián Chivite, Fernándo Chivite, one of Spain's most accomplished winemakers, is ecstatic. He believes "2001 is the best harvest in our history: The yields were low, the concentration is spectacular, and the wines will be extraordinary." Of particular promise is the fruit from Chivite's Arínzano estate, which is ranked among Spain's top vineyards.

Many winemakers in La Rioja, the most important red wine-producing region in Spain, were also elated by the quality of the 2001 vintage, even though production, primarily due to stricter Rioja DO controls, was 25 percent below that of 2000 (a weak vintage for many producers). Francisco Hurtado de Amezaga, technical and production director of La Rioja's oldest winery, the now renascent Marqués de Riscal, thinks the newly renovated bodega's 2001 wines will be noteworthy. "In La Rioja in general, and particularly at Marqués de Riscal, 2001 has been, without a doubt, exceptional," Hurtado says. "Above all, our wines will be characterized by their finesse. Additionally, the quality of the tannins is superior even to the great 1994 vintage. The 2001 wines are rounder and sweeter than the 1994s."

Hurtado, like Torres, is particularly impressed by the quality of the tempranillo: "We sincerely believe that 2001 is a year in which tempranillo has come very close to reaching its greatest potential, if, indeed, it has not done so."

Jésus Madrazo, a member of the family that owns the Compañía Vínicola del Norte de España or CVNE (pronounced Koo-nay) and Contino, a single vineyard Rioja Alavesa "chateau" winery at which he is winemaker, was nothing short of effusive about CVNE's 2001s. "The stability of the color held up magnificently after malolactic fermentation and the purity of the aromatics of each varietal was maintained. We have color, body, alcohol content and beautiful aromas," he enthuses. "We are standing before one of the greatest vintages in history." At Contino, Madrazo claims to have made his best Graciano ever in 2001 - "a wine as dark as ink with 14.2 percent alcohol."

"They haven't seen such levels of color in La Rioja in a long time," observes Mauro's Mariano García, who also consults for such wineries as Bodegas Villabuena, producers of Viña Izadi, a fine, up-and-coming Rioja Alavesa wine. "The raw materials - black wines with fresh fruit flavors - are great, but it will be important to see how the wines evolve before we can be sure that they can be rated historic."

María Martínez Sierra, winemaker at La Rioja's Bodegas Montecillo, is among those withholding judgment on the 2001 harvest in La Rioja. In November, she went on record saying she expected "very good" wines, but felt it was a bit early to proclaim 2001 excellent. By February, she had nudged her assessment up a notch: "I can confirm that 2001 is a very good to excellent vintage. The wines are very deep, intense, well colored and very rich. This is due to several factors: the growers eliminated grapes in late spring (which is key), warm temperatures persisted all season, plus the level of rainfall was ideal." She also believes "the wines have very good concentration, as well as a lot of aging potential," and compares 2001 to the great 1994 vintage. Yet she still has some reservations. "There are already several voices in the area saying that 2001 is even better than the '94, but I do not agree because the big and complex '94 wines are not so easy to repeat," she explains.

Isaac Muga, one of La Rioja's most important producers, says some people in La Rioja are euphoric over wines whose sugar contents soared during the warm days of early October, yet he warns that while the grapes appeared ripe, the essential components that translate to color, aroma and structure were not fully mature. "Those who based the harvesting of their grapes solely on the sugar levels, had some unpleasant surprises after their wines finished malolactic fermentation," he says. Muga, who sources from several vineyards in the higher elevations of La Rioja Alta - in contrast to Jésus Madrazo's situation at the Contino estate along the banks of the Ebro River - says his Graciano harvest was the worst in memory. Still, Muga, who is also very high on his 2000 wines, expects both 2000 and 2001 to be superior in quality to "the mythical 1994 and 1995" crops, which were among the best in the past 20 years.

If the 2001 vintage has an Achilles' heel, it could be those high alcohol levels, and the corresponding acid deficiency that is often the hallmark of such wines. As Muga points out, in some regions wines were made from fruit that was high in sugar, but not phenologically mature.

Having visited all of the main winegrowing areas of northern Spain, Christopher Canaan, president of Europvin, Inc., (importers of such wines as Vega Sicilia, La Rioja Alta and Clos Mogador), underscores Muga's points. "Everyone is happy with the vintage," Canaan reports, "even if it was not always easy to judge the correct maturity of the grapes. The alcohol levels everywhere are high (in some cases at 14.5 to 15 percent before the grapes were phenologically ripe). However," Canaan continues, "all the serious growers were able to cope with this phenomenon resulting in delicious, rich, concentrated wines with masses of ripe fruit, but also good color, structure and balanced acidity."

White wines from 2001, though not being assessed in the same glowing terms as the reds, may also be quite good in many regions. Mariano Fuster of Juve y Camps, one of Spain's top cava producers, lamented the lack of rain (which could signal lower acid levels), but says all the white varieties used for sparkling wines - parelleda, xarello, macabeo (viura) and chardonnay - had a "magnificent aspect, matured at a good pace and were exceptionally healthy." Freixenet, the giant cava producer, reported lower yields and excellent quality, but noted that the "record very dry" year had caused a "light dimunition of acidity." Miguel Torres, who makes some of Spain's best white wines, such as Milmanda Chardonnay, Fransola Sauvignon Blanc and Gran Viña Sol, says 2001, though not excellent for whites, will prove a "very good" year. He is particularly pleased with the harvest from his higher elevation vineyards of garnacha blanca, a native variety that had almost disappeared from Penedés because it was not one of the main grapes in cava, 90 percent of which is produced in that region.

Whether 2001 will be as great as any of the milestone vintages of the past century remains to be seen. But it is clear already that it will produce some truly superlative wines with deep color, exceptional aromatics and superb concentration. And the good news doesn't stop there. Due to the fact that the past few vintages in Spain produced a glut of red wine, many wineries had lowered their prices on unsold wines and subsequently paid far less for top-quality grapes in 2001 than in years past.

Given the perceived quality of the 2001 vintage, prices are sure to be far from cheap, but we will probably not see the absurd prices that marked many of the releases from the mid-1990s.

Looking back on last year, there are many things that most of us would like to forget, but by most accounts, the 2001 harvest in Spain will not be among them. ¶

Insights, information and photographs about Spanish gastronomy, wine, culture and customized tours to Spain, where award-winning writer-photographer Gerry Dawes, author of Sunset in a Glass: Adventures of a Food and Wine Road Warrior in Spain, has been traveling for more than 50 years. Content is from articles, books-in-progress and travel notebooks of Gerry Dawes. Reproduction sprohibited without written permission and author credit.

9/27/2004

9/26/2004

Gentle Corrections Department

A gentle correction to an article in the current October 2004 Restaurant Issue of Gourmet Magazine, an issue that has some excellent articles. (If readers find errors like this in my pieces, please e-mail them to me, I would rather have a little egg on my face than steer you wrong.)

In an article by Alexander Lobrano about Spanish truffles, in which I was glad to see the French own up to getting a lot of their truffles from Spain, the author tells of Joel Dennis, the sous chef from Alain Ducasse's New York restaurant meeting up with his Spanish truffles contact at "Hostal Los Manos, a flourescent-lit truck stop in the backcountry of Catalonia." He then goes on to talk about truffles country and mentions the towns of Mora de Rubielos and Albentosa, which are in the truffles country in the southern foothills of the mountainous El Maestrazgo region in the province of Teruel in Aragón, not Cataluña. Hostal Los Maños, not Manos (hands), is in Albentosa. Los Maños is a colloquial term for the people of Aragón. If the Hostal were named "The Hands," it would be Las Manos, since manos is a feminine noun.

In an article by Alexander Lobrano about Spanish truffles, in which I was glad to see the French own up to getting a lot of their truffles from Spain, the author tells of Joel Dennis, the sous chef from Alain Ducasse's New York restaurant meeting up with his Spanish truffles contact at "Hostal Los Manos, a flourescent-lit truck stop in the backcountry of Catalonia." He then goes on to talk about truffles country and mentions the towns of Mora de Rubielos and Albentosa, which are in the truffles country in the southern foothills of the mountainous El Maestrazgo region in the province of Teruel in Aragón, not Cataluña. Hostal Los Maños, not Manos (hands), is in Albentosa. Los Maños is a colloquial term for the people of Aragón. If the Hostal were named "The Hands," it would be Las Manos, since manos is a feminine noun.

8/09/2004

The Estate Wines of Jean León

by Gerry Dawes

Within the past few years, there has been a significant trend in Spain towards establishing château- and estate-style wineries a la Bordeaux, where all or most of the grapes come from the property surrounding the winery. In Spain, these properties are known as pagos, which are basically agricultural estates based on single-owner vineyard plots in close, often contiguous proximity to one another.

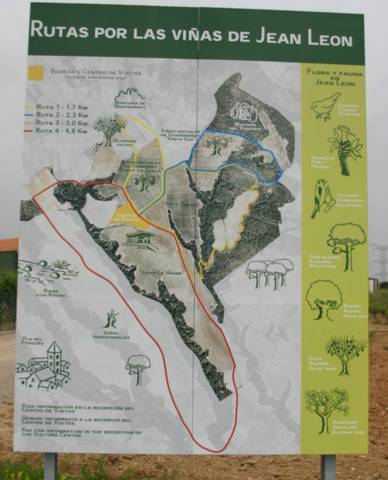

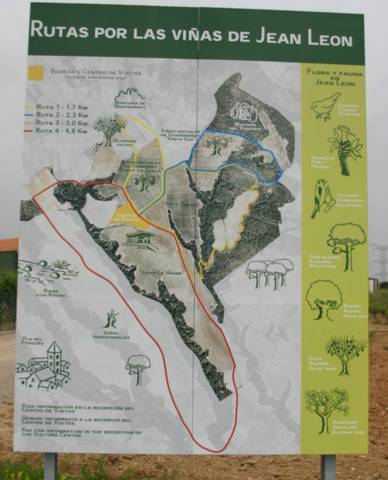

Map of Jean León Estate

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

In La Rioja, the well-known Contino and Remelluri estates were established in the 1970s, but the modern godfather of this concept in Spain was Jean León, a Spanish expatriate who emigrated to the United States, worked in a number of restaurants frequented by movie stars and politicos, and with legendary actor James Dean founded La Scala restaurant, a popular Los Angeles hangout for movie stars.

Jean León came to America, began as a dishwasher in New York and went to work for Frank Sinatra at the singer’s Villa Capri restaurant in Hollywood. He served in the US military during the Korean War, became a naturalized American citizen, and with just $3500 opened La Scala and eventually saw five American presidents and an untold number of movie stars dine there.

In the early 1960s, Jean León used some of the profits from the lucrative La Scala to buy a 370-acre estate near Torrelavit in the highlands of the Catalan wine-growing area of Penedés west of Barcelona. He smuggled cabernet sauvignon vines that he had obtained from Châteaux Lafite-Rothschild, cabernet franc from La Lagune, and chardonnay from Burgundy’s exceptional Corton Charlemagne vineyards (and some pinot noir), ripped up the existing xarel-lo, parellada and macabeu vines (Catalan white grape varieties) ~ much to the surprise of local vine growers, who called him “a crazy American” ~ and planted these foreign varieties on 60 hectares of his land.

View of Jean León Vineyards in the Alt Penedès, Torrelavid (Barcelona)

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

In 1969, Jean León released his first wine, a Cabernet Sauvignon Gran Reserva, almost all of which was sold in his La Scala restaurant or given as gifts to his celebrity friends. It was the first cabernet sauvignon varietal wine made commercially in Spain. In the 1970s, Jean León’s wine, though an anomaly since virtually no Spanish wineries were selling varietal wines, became an underground wine legend. His cabernet sauvignon and cabernet franc-laced blends established a level of quality for those varietals that was unknown in Spain at the time.

Inspired by Jean León’s bold venture, Miguel Torres Riera, then the young French-trained heir to the Bodegas Torres winemaking mantle, soon procured foreign varieties and planted them on his family’s nearby properties. Within a decade his Mas la Plana Black Label Gran Reservas (which eventually were made from 100% cabernet sauvignon) had gained international recognition, even topping the eminent Château Latour in a blind tasting held in Paris.

If Jean León first showed how successful Bordeaux and Burgundy varieties could be in Cataluña, Torres became the leading edge of a wave of cabernet sauvignon, merlot, and chardonnay that washed over the Penedés and in the 1980s spilled over into several emerging wine regions of Spain such as Navarra, Ribera del Duero, Somontano, and Priorato.

Jaume Rovira, who has been the winemaker at Jean León since the bodega was founded in 1964.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Jean León became ill in his sixties and sold his winery and estate to the firm of Miguel Torres. Torres was his friend and the man most responsible for making Jean León’s dream of producing great wines from French grape varieties a huge success in Spain. The wines of the Jean León estate are still made by the original enologist, Jaume Rovira, but the direction and sales of the wines are now in the hands of Miguel Torres Riera’s son, Miguel Torres Maczassek (known as Miguel Torres, Jr.).

Miguel Torres Maczassek, Managing Director of Jean León and son of Miguel Torres Riera, Bodegas Miguel Torres, long one of Spain's most important wineries.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

This writer has long admired the red wines of Jean León and, in recent years, especially a young, fresh, barely-oaked chardonnay (it spends less than two months in oak, just the right touch). In mid-September 2001, with Chef Mark Miller of Santa Fe’s Coyote Cafe, I joined Miguel Torres Jr. at the superb Catalan restaurant Ca l’Isidre in Barcelona for an excellent dinner. We began with that wonderful Jean León white wine, which is sold under the charming name of Petite Chardonnay. With the rest of the meal we drank the wines of Bodegas Miguel Torres, including the supernal, Burgundy-esque Milmanda Chardonnay 1999, the top-of-line Mas la Plana Cabernet Sauvignon 1995, and the multi-faceted Grans Muralles 1997, a new Torres wine from Conca de Barbarà that is a blend of several different recuperated Catalan varieties.

Just over a year later, in November 2002, I met Miguel Torres, Jr., Juan-Ramón Pujol, his American marketing manager, and the representative from Five Star (Jean León’s New York distributor), at Chef Terrance Brennan’s Picholine, one of New York City’s top restaurants. We enjoyed a tasting dinner in the private wine room featuring just the wines produced by Jean León. The dishes, personally prepared by Picholine’s chef de cuisine David Cox, were spectacular and the wines kept pace.

Picholine’s Wine Director Richard Shipman first served us a sample of the fine, fragrant, stylish, boutique Cava (sparkling wine), María Casanova, which, though not made by Jean León or Torres, was from Cataluña and a perfect aperitif to prepare our palates for the tasting. After the Cava, we were served the spicy, floral Terrasola 2001, a delicious chardonnay (85%) and garnacha blanca (15%) blend. Terrasola in Catalan means “small terrace,” the terraced vineyards on which vines were traditionally grown in Cataluña. There are two other wines in the very fine Terrasola line, all of which pair a native variety with a local grape: a rich, peppery syrah-cariñena blend and a muscat-parellada blend.

OVER DINNER AND IN A SUBSEQUENT INTERVIEW, Torres, Jr. and I talked about the Jean León estate, in which he has a significant personal investment, both financially and professionally.

WFSN: Could you tell me a few things about the Jean León bodega, vineyards, and wines?

MT, Jr.: Yes, I think that we have something very good, which are some of the oldest vines of cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc and merlot in the region. The cabernet is already 39 years old, and the soil does not provide many nutrients, so the vines are stressed and are producing the best quality for us.

WFSN: What changes have you implemented?

MT, Jr.: Since 1994 we have done a lot of work in the winery. We first started by acquiring new oak barrels, both French and American, and reorganizing the installations. During 2000, 2001 and 2002 we made the biggest improvements. We decreased even more the production, lowering it to 4,500 kg per hectare (just over 2 tons per acre) and less for the Cabernet Sauvignon Gran Reserva. I did not want irrigation because I believe that we have to show what the vines can give us naturally. The second thing I did was to invest in a new temperature-con-trolled room, so that we can perfectly control the fermentation of our barrel-fermented chardonnay. It also helps a lot to cool down all grapes before crushing them in the press. The third thing was to maintain the oak barrels even more carefully, I liked some good American oak for the reserva, but I liked French oak better for the longer-lived gran reserva, so now I use only new French small-grain oak barrels for the gran reserva and the chardonnay. Also for the reservas and the gran reservas, I thought that they were sometimes not expressing the primary aromas clearly since they were aged for up to two years in new oak. We decided that only for the first year would they be aged in new oak and then we would put them in 4- or 5-year old barrels the second year so that they would not absorb too much oak flavor.

WFSN: Anything else?

MT, Jr.: Yes, I wanted the cellars to be cooler at Jean León! So, now with new equipment we can regulate the temperature not only during the fermentation, but also in the cellar and even in the grape pick up area, which is also very important. And on November 9th we started operations in a new visitor’s center at Jean León, located in the heart of the vineyards with a breathtaking view of the Penedés region. So now Jean León is open to all the wine lovers who want to visit us.

AS ONE MIGHT EXPECT FROM THE PRICE DIFFERENTIAL, the Jean León estate wines were the stars of the evening at Picholine. There was the spicy, rich, buttery, very classy Jean León Chardonnay 2000 made from grapes grown at Viña Gigi, a 40-acre chardonnay vineyard, which is the oldest chardonnay vineyard in Spain.

The Jean León Merlot 1999, a 100% merlot varietal, was a deep blackberry-colored wine with rich, spicy, fruity merlot flavors and a long tannic finish that showed it would benefit from more aging. Jean León’s merlot vines, now ten years old, were a late addition to the estate.

Jean León Cabernet Sauvignon 1996, a blend of 85% cabernet sauvignon and 15% cabernet franc, was a clean, clear medium blackberry color, had a nice mint and cedar nose, showed lovely, rich blackberry and chocolate flavors on the palate and had a long spicy, well-stuctured finish.

The nicely structured Jean León Cabernet Sauvignon Reserva 1995 (same blend), a serious black raspberry-colored wine with a minty, eucalyptus nose, chocolate, ripe fruit flavors and earthy hints of cabernet franc, spent 2 years in oak and like a good Bordeaux, will benefit from cellaring.

The exceptional Jean León Cabernet Sauvignon Gran Reserva 1994 is basically the same grape blend as the reservas, but it all comes from specially selected lots made from the oldest vines grown on the estate’s La Scala vineyard. This dark, plummy, blackberry colored wine has a deep, ripe nose and luscious, delicious, complex flavors and firm structure that puts it on the level with many great Bordeaux châteaux wines.

We finished our meal at Picholine with a selection of superb Spanish cheeses and a selection of older cabernet sauvignon wines from Jean León, including the still vital, but mellow 1985; the still-closed, Bordeaux-esque 1979; and the excellent minty, complex 1975.

During the heyday of La Scala restaurant in Beverly Hills, Jean León became known as “the wine of the stars.” Now, some thirty years later, the wines of Jean León are showing their own star potential.

Gerry Dawes has been writing about Spanish wine, food and culture for more than 25 years.

Within the past few years, there has been a significant trend in Spain towards establishing château- and estate-style wineries a la Bordeaux, where all or most of the grapes come from the property surrounding the winery. In Spain, these properties are known as pagos, which are basically agricultural estates based on single-owner vineyard plots in close, often contiguous proximity to one another.

Map of Jean León Estate

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

In La Rioja, the well-known Contino and Remelluri estates were established in the 1970s, but the modern godfather of this concept in Spain was Jean León, a Spanish expatriate who emigrated to the United States, worked in a number of restaurants frequented by movie stars and politicos, and with legendary actor James Dean founded La Scala restaurant, a popular Los Angeles hangout for movie stars.

Jean León came to America, began as a dishwasher in New York and went to work for Frank Sinatra at the singer’s Villa Capri restaurant in Hollywood. He served in the US military during the Korean War, became a naturalized American citizen, and with just $3500 opened La Scala and eventually saw five American presidents and an untold number of movie stars dine there.

In the early 1960s, Jean León used some of the profits from the lucrative La Scala to buy a 370-acre estate near Torrelavit in the highlands of the Catalan wine-growing area of Penedés west of Barcelona. He smuggled cabernet sauvignon vines that he had obtained from Châteaux Lafite-Rothschild, cabernet franc from La Lagune, and chardonnay from Burgundy’s exceptional Corton Charlemagne vineyards (and some pinot noir), ripped up the existing xarel-lo, parellada and macabeu vines (Catalan white grape varieties) ~ much to the surprise of local vine growers, who called him “a crazy American” ~ and planted these foreign varieties on 60 hectares of his land.

View of Jean León Vineyards in the Alt Penedès, Torrelavid (Barcelona)

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

In 1969, Jean León released his first wine, a Cabernet Sauvignon Gran Reserva, almost all of which was sold in his La Scala restaurant or given as gifts to his celebrity friends. It was the first cabernet sauvignon varietal wine made commercially in Spain. In the 1970s, Jean León’s wine, though an anomaly since virtually no Spanish wineries were selling varietal wines, became an underground wine legend. His cabernet sauvignon and cabernet franc-laced blends established a level of quality for those varietals that was unknown in Spain at the time.

Inspired by Jean León’s bold venture, Miguel Torres Riera, then the young French-trained heir to the Bodegas Torres winemaking mantle, soon procured foreign varieties and planted them on his family’s nearby properties. Within a decade his Mas la Plana Black Label Gran Reservas (which eventually were made from 100% cabernet sauvignon) had gained international recognition, even topping the eminent Château Latour in a blind tasting held in Paris.

If Jean León first showed how successful Bordeaux and Burgundy varieties could be in Cataluña, Torres became the leading edge of a wave of cabernet sauvignon, merlot, and chardonnay that washed over the Penedés and in the 1980s spilled over into several emerging wine regions of Spain such as Navarra, Ribera del Duero, Somontano, and Priorato.

Jaume Rovira, who has been the winemaker at Jean León since the bodega was founded in 1964.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

Jean León became ill in his sixties and sold his winery and estate to the firm of Miguel Torres. Torres was his friend and the man most responsible for making Jean León’s dream of producing great wines from French grape varieties a huge success in Spain. The wines of the Jean León estate are still made by the original enologist, Jaume Rovira, but the direction and sales of the wines are now in the hands of Miguel Torres Riera’s son, Miguel Torres Maczassek (known as Miguel Torres, Jr.).

Miguel Torres Maczassek, Managing Director of Jean León and son of Miguel Torres Riera, Bodegas Miguel Torres, long one of Spain's most important wineries.

Gerry Dawes copyright 2004

This writer has long admired the red wines of Jean León and, in recent years, especially a young, fresh, barely-oaked chardonnay (it spends less than two months in oak, just the right touch). In mid-September 2001, with Chef Mark Miller of Santa Fe’s Coyote Cafe, I joined Miguel Torres Jr. at the superb Catalan restaurant Ca l’Isidre in Barcelona for an excellent dinner. We began with that wonderful Jean León white wine, which is sold under the charming name of Petite Chardonnay. With the rest of the meal we drank the wines of Bodegas Miguel Torres, including the supernal, Burgundy-esque Milmanda Chardonnay 1999, the top-of-line Mas la Plana Cabernet Sauvignon 1995, and the multi-faceted Grans Muralles 1997, a new Torres wine from Conca de Barbarà that is a blend of several different recuperated Catalan varieties.

Just over a year later, in November 2002, I met Miguel Torres, Jr., Juan-Ramón Pujol, his American marketing manager, and the representative from Five Star (Jean León’s New York distributor), at Chef Terrance Brennan’s Picholine, one of New York City’s top restaurants. We enjoyed a tasting dinner in the private wine room featuring just the wines produced by Jean León. The dishes, personally prepared by Picholine’s chef de cuisine David Cox, were spectacular and the wines kept pace.

Picholine’s Wine Director Richard Shipman first served us a sample of the fine, fragrant, stylish, boutique Cava (sparkling wine), María Casanova, which, though not made by Jean León or Torres, was from Cataluña and a perfect aperitif to prepare our palates for the tasting. After the Cava, we were served the spicy, floral Terrasola 2001, a delicious chardonnay (85%) and garnacha blanca (15%) blend. Terrasola in Catalan means “small terrace,” the terraced vineyards on which vines were traditionally grown in Cataluña. There are two other wines in the very fine Terrasola line, all of which pair a native variety with a local grape: a rich, peppery syrah-cariñena blend and a muscat-parellada blend.

OVER DINNER AND IN A SUBSEQUENT INTERVIEW, Torres, Jr. and I talked about the Jean León estate, in which he has a significant personal investment, both financially and professionally.

WFSN: Could you tell me a few things about the Jean León bodega, vineyards, and wines?

MT, Jr.: Yes, I think that we have something very good, which are some of the oldest vines of cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc and merlot in the region. The cabernet is already 39 years old, and the soil does not provide many nutrients, so the vines are stressed and are producing the best quality for us.

WFSN: What changes have you implemented?

MT, Jr.: Since 1994 we have done a lot of work in the winery. We first started by acquiring new oak barrels, both French and American, and reorganizing the installations. During 2000, 2001 and 2002 we made the biggest improvements. We decreased even more the production, lowering it to 4,500 kg per hectare (just over 2 tons per acre) and less for the Cabernet Sauvignon Gran Reserva. I did not want irrigation because I believe that we have to show what the vines can give us naturally. The second thing I did was to invest in a new temperature-con-trolled room, so that we can perfectly control the fermentation of our barrel-fermented chardonnay. It also helps a lot to cool down all grapes before crushing them in the press. The third thing was to maintain the oak barrels even more carefully, I liked some good American oak for the reserva, but I liked French oak better for the longer-lived gran reserva, so now I use only new French small-grain oak barrels for the gran reserva and the chardonnay. Also for the reservas and the gran reservas, I thought that they were sometimes not expressing the primary aromas clearly since they were aged for up to two years in new oak. We decided that only for the first year would they be aged in new oak and then we would put them in 4- or 5-year old barrels the second year so that they would not absorb too much oak flavor.

WFSN: Anything else?

MT, Jr.: Yes, I wanted the cellars to be cooler at Jean León! So, now with new equipment we can regulate the temperature not only during the fermentation, but also in the cellar and even in the grape pick up area, which is also very important. And on November 9th we started operations in a new visitor’s center at Jean León, located in the heart of the vineyards with a breathtaking view of the Penedés region. So now Jean León is open to all the wine lovers who want to visit us.

AS ONE MIGHT EXPECT FROM THE PRICE DIFFERENTIAL, the Jean León estate wines were the stars of the evening at Picholine. There was the spicy, rich, buttery, very classy Jean León Chardonnay 2000 made from grapes grown at Viña Gigi, a 40-acre chardonnay vineyard, which is the oldest chardonnay vineyard in Spain.

The Jean León Merlot 1999, a 100% merlot varietal, was a deep blackberry-colored wine with rich, spicy, fruity merlot flavors and a long tannic finish that showed it would benefit from more aging. Jean León’s merlot vines, now ten years old, were a late addition to the estate.

Jean León Cabernet Sauvignon 1996, a blend of 85% cabernet sauvignon and 15% cabernet franc, was a clean, clear medium blackberry color, had a nice mint and cedar nose, showed lovely, rich blackberry and chocolate flavors on the palate and had a long spicy, well-stuctured finish.

The nicely structured Jean León Cabernet Sauvignon Reserva 1995 (same blend), a serious black raspberry-colored wine with a minty, eucalyptus nose, chocolate, ripe fruit flavors and earthy hints of cabernet franc, spent 2 years in oak and like a good Bordeaux, will benefit from cellaring.

The exceptional Jean León Cabernet Sauvignon Gran Reserva 1994 is basically the same grape blend as the reservas, but it all comes from specially selected lots made from the oldest vines grown on the estate’s La Scala vineyard. This dark, plummy, blackberry colored wine has a deep, ripe nose and luscious, delicious, complex flavors and firm structure that puts it on the level with many great Bordeaux châteaux wines.

We finished our meal at Picholine with a selection of superb Spanish cheeses and a selection of older cabernet sauvignon wines from Jean León, including the still vital, but mellow 1985; the still-closed, Bordeaux-esque 1979; and the excellent minty, complex 1975.

During the heyday of La Scala restaurant in Beverly Hills, Jean León became known as “the wine of the stars.” Now, some thirty years later, the wines of Jean León are showing their own star potential.

Gerry Dawes has been writing about Spanish wine, food and culture for more than 25 years.

8/07/2004

Rias Baixas Wines

Rías Baixas Wines

Rías Baixas Wines On a ten-day tasting trip last spring through six wine growing regions of northwestern Spain, I got a crash course in just how promising Spanish native varietals can be in the Atlantic Ocean- influenced climates of Galicia (Rías Baixas, Ribeira Sacra and Valdeorras) and Castilla-León (Bierzo, Toro and Rueda). In this post I will cover Rías Baixa. In subsequent posts, I cover the others.

First, I flew from Madrid to Santiago de Compostela, the monumental destination city at the end of the Camino de Santiago, the medieval pilgrimage route that runs from France down into the Iberian Peninsula and then more than 600 miles across northern Spain. From Santiago, I began my visit to emerald-green Galicia's Rías Baixas, where I tasted some 50 wines, including some superb 100% Albariños. Pazo de Señorans, Fillaboa, Do Ferreiro, Lagar Pedregales, Palacio de Fefiñanes, Lusco, and Pazo de Barrantes, not only reinforced my belief in the excellence of this white native varietal, it alerted me to aspects of albariño's versatility and ageworthiness of which I was unaware.

From my tastings of barrel fermented Rías Baixas white wines, I re-confirmed my belief that new oak does not significantly enhance these fresh, fruity wines; in fact, it often obscures their fruit and charm. Most wineries are experimenting with barrel-fermented (a current fad) Albariños, but hardly any of them were better than the bodega's un-oaked Albariño.

I also discovered that two notable producers, Pazo de Señorans and Palacio de Fefiñanes, were making Albariños that see no new oak and are eminently ageworthy. Pazo de Señorans produced a stunning 1996 Albariño aged on the lees in stainless steel for three years, which is undoubtedly the greatest Rías Baixas wine I have tasted. Palacio de Fefiñanes showed a superb vertical lineup (from 2001 through 1996) of Albariños aged in large used oak vats. Another surprise was a luscious, sweet, complex, vendimia tardia (late harvest) Albariño made as an experiment at Pazo de Barrantes.

Galician Seafood & Albarino

The Rías Baixas denominación de origen is composed of five subzones: Val do Salnés, Soutomaior, O Rosal, Condado de Tea, and Ribeira do Ulla, the newest of the designated wine growing areas. Surrounded on three sides by the Atlantic Ocean, the Ría de Arousa and the Ría de Pontevedra, the area known as Val do Salnés, with more than 60% of Rías Baixas's registered vineyards, is the most important of the five, followed by Condado de Tea and O Rosal, both along the Miño river. Because of Galicia's high rainfall and humidity, vines are trained on tall wire trellises, which are usually anchored by granite or concrete posts. The grapes are grown several feet off the ground to allow for maximum air circulation, which promotes even ripening and helps prevent rot and associated vine and grape afflictions.

To use the Albariño varietal designation on a label, in all five Rías Baixas subzones a wine must be 100% albariño. Since 94% of just over 5900 acres of registered vineyards in the Rías Baixas DO are albariño, this is often a moot point. By law, other white Rías Baixas-designated wines of must contain a minimum of 70% Albariño. The remaining 30% of the blend is usually composed of one or more of the other authorized, preferred grape varieties - - treixadura, loureira, and caiño blanco (some godello, torrontés, and marqués grapes are also authorized) - - which add different aromas, body, and often more complexity to the wines.

Although Albariños are among the world's finest single-varietal white wines, the Rías Baixas blends often match them in quality. In tasting albariño-treixadura blends such as Adegas Galegas's Veigadares, Valmiñor's Dávila, Marqués de Vizhoja's Señor de Folla Verde, in the Condado de Tea subzone of Rías Baixas, along the Miño River that is the Galicia's border with Portugal, and albariño, loureiro, and treixadura blends such as Terras Gauda, Santiago Ruíz, Pazo San Mauro, and in the O Rosal subzone, I also saw significant potential in loureiro and treixadura as blending grapes which add complexity to albariño-based wines.

It is not politically incorrect to call Rías Baixas wines of the most feminine in Spain, especially since the consejo regulador's president is María Soledad Bueno (the owner of Pazo de Señorans) and many top wines are made by women enologists, including Isabel Salgado (Granja Fillaboa), Cristina Mantilla (Adegas Galegas - Veigadares), Angela Martín (Castro Martín- Casal Caiero), María del Pilar Jiménez (Pazo de Barrantes), Ana Martín (Salnesur - Condes de Albarei), Ana Oliveira (Terras Guada), Ana Quintela (Pazo de Señorans), and María Luisa Freire (Santiago Ruíz).

Rías Baixas Albariños and albariño-based blends are some of the most versatile, delicious, food-friendly, and least intimidating wines in the market. They usually are a lovely green-tinged straw color and their fruity albariño aromas are reminiscent of white peaches, pears, apricots or pineapple. On the palate they are fruity and often luscious, but finish dry. The fruit is usually beautifully balanced by a fine-edged underpining of acidity and the wines exhibit lovely, complex, mineral-laced flavors in the finish. These qualities make them ideal matches for a wide variety of modern and traditional dishes, as well as delicious wines for sipping as an aperitif or to accompany tapas, Spain's wide variety of little dishes.

Galician Seafood & Pazo de Senorans

Albariño blends are also supernal companions to the splendid seafood that Galicia was known for before the criminal actions of the Prestige single-hull oil tanker, which sank off the coast of Spain in November 2002, destroyed the most important source of prime shellfish in Europe, and ruined the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of hard-working Spaniards and Portuguese, including those who work in the superb marisquerías, or seafood restaurants of these two maritime countries. I am happy to say in this update on August 7, 2004, the Galicians, through a Herculean effort have recuperated much of their fishing grounds. --Gerry Dawes©2003

Rías Baixas Wines On a ten-day tasting trip last spring through six wine growing regions of northwestern Spain, I got a crash course in just how promising Spanish native varietals can be in the Atlantic Ocean- influenced climates of Galicia (Rías Baixas, Ribeira Sacra and Valdeorras) and Castilla-León (Bierzo, Toro and Rueda). In this post I will cover Rías Baixa. In subsequent posts, I cover the others.

First, I flew from Madrid to Santiago de Compostela, the monumental destination city at the end of the Camino de Santiago, the medieval pilgrimage route that runs from France down into the Iberian Peninsula and then more than 600 miles across northern Spain. From Santiago, I began my visit to emerald-green Galicia's Rías Baixas, where I tasted some 50 wines, including some superb 100% Albariños. Pazo de Señorans, Fillaboa, Do Ferreiro, Lagar Pedregales, Palacio de Fefiñanes, Lusco, and Pazo de Barrantes, not only reinforced my belief in the excellence of this white native varietal, it alerted me to aspects of albariño's versatility and ageworthiness of which I was unaware.

From my tastings of barrel fermented Rías Baixas white wines, I re-confirmed my belief that new oak does not significantly enhance these fresh, fruity wines; in fact, it often obscures their fruit and charm. Most wineries are experimenting with barrel-fermented (a current fad) Albariños, but hardly any of them were better than the bodega's un-oaked Albariño.

I also discovered that two notable producers, Pazo de Señorans and Palacio de Fefiñanes, were making Albariños that see no new oak and are eminently ageworthy. Pazo de Señorans produced a stunning 1996 Albariño aged on the lees in stainless steel for three years, which is undoubtedly the greatest Rías Baixas wine I have tasted. Palacio de Fefiñanes showed a superb vertical lineup (from 2001 through 1996) of Albariños aged in large used oak vats. Another surprise was a luscious, sweet, complex, vendimia tardia (late harvest) Albariño made as an experiment at Pazo de Barrantes.

Galician Seafood & Albarino

The Rías Baixas denominación de origen is composed of five subzones: Val do Salnés, Soutomaior, O Rosal, Condado de Tea, and Ribeira do Ulla, the newest of the designated wine growing areas. Surrounded on three sides by the Atlantic Ocean, the Ría de Arousa and the Ría de Pontevedra, the area known as Val do Salnés, with more than 60% of Rías Baixas's registered vineyards, is the most important of the five, followed by Condado de Tea and O Rosal, both along the Miño river. Because of Galicia's high rainfall and humidity, vines are trained on tall wire trellises, which are usually anchored by granite or concrete posts. The grapes are grown several feet off the ground to allow for maximum air circulation, which promotes even ripening and helps prevent rot and associated vine and grape afflictions.

To use the Albariño varietal designation on a label, in all five Rías Baixas subzones a wine must be 100% albariño. Since 94% of just over 5900 acres of registered vineyards in the Rías Baixas DO are albariño, this is often a moot point. By law, other white Rías Baixas-designated wines of must contain a minimum of 70% Albariño. The remaining 30% of the blend is usually composed of one or more of the other authorized, preferred grape varieties - - treixadura, loureira, and caiño blanco (some godello, torrontés, and marqués grapes are also authorized) - - which add different aromas, body, and often more complexity to the wines.

Although Albariños are among the world's finest single-varietal white wines, the Rías Baixas blends often match them in quality. In tasting albariño-treixadura blends such as Adegas Galegas's Veigadares, Valmiñor's Dávila, Marqués de Vizhoja's Señor de Folla Verde, in the Condado de Tea subzone of Rías Baixas, along the Miño River that is the Galicia's border with Portugal, and albariño, loureiro, and treixadura blends such as Terras Gauda, Santiago Ruíz, Pazo San Mauro, and in the O Rosal subzone, I also saw significant potential in loureiro and treixadura as blending grapes which add complexity to albariño-based wines.

It is not politically incorrect to call Rías Baixas wines of the most feminine in Spain, especially since the consejo regulador's president is María Soledad Bueno (the owner of Pazo de Señorans) and many top wines are made by women enologists, including Isabel Salgado (Granja Fillaboa), Cristina Mantilla (Adegas Galegas - Veigadares), Angela Martín (Castro Martín- Casal Caiero), María del Pilar Jiménez (Pazo de Barrantes), Ana Martín (Salnesur - Condes de Albarei), Ana Oliveira (Terras Guada), Ana Quintela (Pazo de Señorans), and María Luisa Freire (Santiago Ruíz).

Rías Baixas Albariños and albariño-based blends are some of the most versatile, delicious, food-friendly, and least intimidating wines in the market. They usually are a lovely green-tinged straw color and their fruity albariño aromas are reminiscent of white peaches, pears, apricots or pineapple. On the palate they are fruity and often luscious, but finish dry. The fruit is usually beautifully balanced by a fine-edged underpining of acidity and the wines exhibit lovely, complex, mineral-laced flavors in the finish. These qualities make them ideal matches for a wide variety of modern and traditional dishes, as well as delicious wines for sipping as an aperitif or to accompany tapas, Spain's wide variety of little dishes.

Galician Seafood & Pazo de Senorans

Albariño blends are also supernal companions to the splendid seafood that Galicia was known for before the criminal actions of the Prestige single-hull oil tanker, which sank off the coast of Spain in November 2002, destroyed the most important source of prime shellfish in Europe, and ruined the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of hard-working Spaniards and Portuguese, including those who work in the superb marisquerías, or seafood restaurants of these two maritime countries. I am happy to say in this update on August 7, 2004, the Galicians, through a Herculean effort have recuperated much of their fishing grounds. --Gerry Dawes©2003

Catavino: Sherry Glass

Catavino at Vinicola Hidalgo

Gerry Dawes Copyright 2008

Manzanilla Sherry glass

A smaller tulip-shaped glass called a catavino is used for sherry. Ideally, they should be 5-6 ounce glasses, but you should only fill them about half full (2-3 ounces of sherry), though this thristy caballero on horseback at the Feria de Sevilla has his catavino nearly full.

Gerry Dawes Copyright 2004

An alternative is a tulip-shaped 6-ounce Champagne glass will do nicely. The Champagne flute should be one that curves in at the top, not one that flares out, so that you can more fully enjoy the wonderful fragrant smells of sherry.

7/27/2004

Back to The Future - Wine Enthusiast, Sept. 2002

Spain: Looking Back To The Future By GERRY DAWES

First Appeared in The Wine Enthusiast, Sept. 2002

Three-star restaurants, cultish boutique wines and appreciative, affluent consumers: europe’s gastronomic epicenter just may be shifting to España.

When I first began traveling the wine roads of Spain in the early 1970s, the state of Spanish wine and food was dramatically different than it is today. Most wineries were rustic and used time-honored, often ancient, techniques to vinify grapes and age their wines. They were imbued with the romance of Old Spain and were aged in old barrels, often in moldy, cobweb-laced, ancient caves. I loved tasting them. However, while some of the wines were excellent on the spot when served with down-to-earth Spanish food like milk-fed baby lamb chops grilled over vine cuttings, air-cured hams and artisan cheeses, many of the wines were not built to travel.

Back then, there were wonderful down-home restaurants with legendary regional dishes that were often the object of gastronomic pilgrimages by Spanish aficionados. The meals included roast suckling pig and lamb, black rice paellas, fat pochas beans cooked with country chorizo and quail, and shellfish hot off a flat grill. But many ordinary restaurants were plagued with poorly trained cooks using substandard cooking oils instead of the quality Spanish olive oil that gourmands so appreciate today.

In fact, many upscale restaurants often offered so-called “continental” cuisine that seemed designed to protect foreign tourists from the horrors of olive oil, garlic and other ingredients that are now highly regarded elements of the Mediterranean diet.

In those days I often wished that the Spaniards would figure out how to get those deeply flavored, ruby-colored Duero Valley wines—in Aranda de Duero, served in earthenware pitchers—in shape to sell in foreign markets. And those wonderful Manzanilla Sherries that I drank on Sanlúcar de Barrameda’s Bajo de Guía beach at sunset with exquisite grilled langostinos (giant prawns): Would we ever be able to get fresh Manzanilla in America? And what about those deeply flawed, but incredibly promising backcountry Priorato wines I drank with grilled rabbit and allioli in the 1980s?

Up until the early 1990s, the main players in the export markets remained the well-aged red wines from Rioja, Sherries from Jerez, cheap sparkling wines from Cataluña, the wines of Miguel Torres, Sr. and the near-mythical Vega Sicilia, then Spain’s most expensive and mysterious wine. For most Americans, Spanish wines conjured up visions of a hot Mediterranean country that produced robust oak-aged reds, mediocre whites, cheap bubbly and Sherries that usually sat on restaurant and retail shelves until they were shot. Since then, there has been an explosion in the quality and breadth of Spanish wines comparable to that of California in the 1970s and 1980s. And many experts are now beginning to believe that the food in Spain these days is better than it is in any other country in Europe.

Poised on the Edge

Until the mid-1970s, the octogenarian dictator Francisco Franco was ostensibly still running the country; to outsiders, Spain seemed mired inextricably in the past. At that time, Spaniards were poised on the edge, precariously balanced between that backward post-Civil War period—an era they desperately wanted to shake—and an uncertain future, one that the many brighter lights in Spain thought was filled with promise.

During that unstable political climate, a few were willing to take a chance on the future of Spanish wine. Years earlier, Jean León, a Spanish expatriate and Los Angeles restaurateur, had already shown what could be done in Spain with estate-grown wines, producing several acclaimed Cabernet Sauvignon-based reds and Chardonnays in Penedès. In Rioja, in 1970, Henri Forner, a Bordeaux producer (Château Larose-Trintadon and Château Camensac) whose Valencian family was exiled to France during the Spanish Civil War, took the plunge and founded the Unión Viti-Vinícola, whose brand Marqués de Cáceres became a legendary success. Sherry producers such as Domecq (Marqués de Arienzo), González Byass (Beronia) and Osborne (Montecillo) either founded or purchased new bodegas in Rioja and, in 1973, Bilbao industrialist Luís Olarra founded the state-of-the-art Bodegas Olarra, one of the greatest Rioja wineries of the period.

Sherry country itself experienced something on the order of a coup d’etat as more than 50 percent of the production was gobbled up by Rumasa, a giant company with Sherry-family roots. Soon Cava country bubbled over as Rumasa moved in and took over 40 percent of the production. Building Spain’s first truly international brand of oak-aged table wines, the Torres family continued to invest profits back into their company in Vilafranca del Penedès, and year by year young Miguel Torres, Jr. made his presence increasingly felt on the style and quality of the wines. Codorníu, the Cava giant, planted a sizeable estate vineyard with Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay in Lerida province in the foothills of the Catalan Pyrenees. It then became its own denominación de origen, Costers del Segre. And, in a little-known area of the Duero Valley, Alejandro Fernández, a producer of agricultural equipment with a taste for rich, silky, but balanced and ageworthy wines, began making Pesquera, which became Spain’s first great overnight international star in the 1980s. By the mid 1990s, Álvaro Palacios (Clos Dofi and L’Ermita), Carles Pastrana (Clos de L’Obac), René Barbier (Clos Mogador) and Daphne Glorian (Clos Erasmus) had begun to put the dark, powerful wines of Priorato on the map.

Gastronomy and Winemaking Flourish

Following the death of Franco in 1975 and several more years of political turmoil, Spaniards began to excel in business, the arts, cinema, architecture, fashion and even golf. Fueled by a newly affluent and steadily expanding middle class armed with credit cards and buoyed by a surprising jump in the number of English speakers, Spain experienced an unprecedented wine and food boom that hasn’t let up. The country’s gregarious citizens who always loved to wine and dine suddenly began to take a serious interest; wine and gastronomic publications, wine clubs, wine-tasting groups and wine courses proliferated. Spaniards, like their American and European counterparts, began to see wine and food as desirable career choices; enology courses and cooking schools cropped up around the country.

Jesús Madrazo is an exemplar of the new wave in the Spanish wine world. He is a thirty-something member of one of the regal families of classic Rioja wine—CUNE (Compañía Vínicola del Norte de España)—and is one of Spain’s brightest new wine stars. Madrazo is currently the general manager of Contino, a CUNE-affiliated winery and one of the first to embrace the Bordeaux-style single-estate concept in the early 1970s. His three wines, Contino Reserva (which becomes more elegant and stylish each year), the single-plot El Olivo and the 100 percent Graciano (probably the best example of that classic Rioja varietal made) have earned serious national and international attention.

“In 1985, when I was working on my engineer in agronomy degree,” Madrazo remembers, “it was difficult to find any wine-tasting courses; now there are hundreds around the country. There were just a few magazines specializing in wine and food, now there are at least 10. Specialty wine shops hardly existed, now there are hundreds.”

It took a couple of decades, but to longtime observers, Spain’s quantum leap happened with surprising speed. In the March 2002 issue of Sobremesa (one of Spain’s top food and wine magazines), Editor-in-Chief Ernesto Portuondo reflected on how the Rioja-Jerez-Cava trio dominated the early articles of the magazine and how much things have changed. In just over 15 years, he wrote, “Spanish customs, polemics, language, understanding, the national panorama and, above all, wines have changed so much that it is difficult to believe that we are talking about the same country.”

These days the whole world is talking about Spain’s latest wine-and-food miracle. A Basque restaurant was recently awarded Michelin’s highest rating—three rosettes. That makes four Spanish restaurants with three each (the newest, Martín Berasategui, joins Arzak in San Sebastián; El Racó de Can Fabes, just outside Barcelona; and the famous El Bullí, two hours north of Barcelona). The indispensable dining guide in Spain, the Madrid-based Gourmetour, rates restaurants on a 10-point scale and lists a dozen establishments with nine or more points, which is their equivalent of Michelin’s three rosettes. Some wineries, such as Marqués de Murrieta, stillbottle their gran reservas by hand.

“The most innovative cooking in Europe is being done in Spain nowadays,” says Mark Miller, chef at Coyote Café, which has locations in Santa Fe and Las Vegas. Miller has been to Spain a dozen times in the past few years. “Not only are the cooking techniques and presentations as creative as at other top restaurants in the world, but the whimsical and creative design and casual atmosphere make dining a true pleasure for the mind and the senses, and not just an exercise in status. The Spanish passion for living and expression makes eating in Spain a true delight.”

According to Michael Lomonaco, former executive chef at Windows on the World and now a consulting chef at Manhattan’s new Latino restaurant, Noche, “Spain is a must for everyone serious about food and wine. I am impressed with how Spain’s distinctive regional cuisines seem so naturally suited to the wide spectrum of Spanish wines.”

A Trend in Pagos and Estates

That wide spectrum is reached, in part, because of the thousands of old-vine vineyards in very special, if previously underdeveloped, microclimates such as Rías Baixas, Priorato, Bierzo and Ribeira Sacra. These are places in the Texas-sized country where long-acclimatized grape varieties are rooted in the kinds of soils that rival the terroirs of France.

Some of the recently released wines from these microclimates have been so impressive on a world-class scale that they are making real headway in the American market. In addition to the traditional favorites from Rioja and brands established in the late 20th century, reds from the Ribera del Duero, Priorato, Navarra and Penedés and white wines from Rías Baixas, Rueda and Penedés have made significant inroads lately. And there is a steady buzz about the new-wave wines coming out of these areas, especially those from single vineyards or pagos.

Andrés Proensa, one of Spain’s top wine writers, calls the single-vineyard movement one of the most dominant trends in modern Spanish wines. Historically, Spanish wine producers paid little attention to single-vineyard estates. In the early 1970s, Rioja had only the fledgling Remelluri and Contino estates; Cataluña had only Jean León and Miguel Torres’s Mas La Plana Cabernet Sauvignon vineyards. Today, there are too many to count.“This is the most important change in Spanish wine,” Proensa says, “producers at the vanguard are looking more towards vineyard quality now and are relying less on using technology to manipulate the wine in their cellars.”

Even in Rioja, where wines are still largely made by a modified négociant system in which some grapes and wine are purchased, the process is undergoing dramatic changes. Many of the larger bodegas have augmented their grape sources by purchasing existing quality vineyards, planting new ones and cementing relationships with quality cosecheros—those who have not yet founded their own small estate-based wineries. These are the same viticulturalists who have been growing grapes for the larger wineries to increasingly demanding specifications.

Proensa, who authored the annual Guía de Oro de Los Vinos de España for several years and will begin publishing the Guía Proensa (de Los Mejores Vinos de España) next year, says that for the past decade there has also been a distinct trend toward what he calls “Parkerian fever” as many Spanish winemakers have been making styles seemingly preferred by Robert M. Parker, Jr. But Proensa acknowledges that many top producers are beginning to let up on the big, ripe, blockbuster wines—wines he describes as having a “bruising character”—in favor of those with “a more finely drawn style that is more subtle, but still rich in color, flavor and aromas.”

While backward winemaking technology ceased to be an issue in Spain several years ago, Proensa believes that technical progress has reached its ceiling. The latest advances have been rapidly assimilated in Spain as well as elsewhere, even at traditional Rioja wineries such as Marqués de Riscal (founded 1860), CUNE (1879) and La Rioja Alta (1896). While having state-of-the-art facilities has obvious benefits, Proensa explains this development has had its downside.

“The reliance on modern winemaking technology has a tendency to make wines that are too uniform,” Proensa says. (Much the same can be said for the widespread, heavy-handed use of new French oak in Spain.) “The smartest Spanish enologists are looking to combine many elements—soil, grape varieties, climate, proper vineyard cultivation, production methods and different types of oak—in order to make more harmonious wines with distinct personalities.”

Yet Spain’s steady stream of new wines could become an embarrassment of riches. A bewildering array of new wines from diverse and little-known regions around Spain are constantly entering the market. No longer confined to specialty shops, wines from La Mancha, Toro, Somontano, Jumilla and other even more obscure regions are becoming widely distributed and many top restaurants feature them on their wine lists.

Three Steps Forward and Two Back?

It is difficult to keep up with the hundreds of wines that are being produced in Spain. And while a vast number are very good, there are a few unfortunate characteristics common in many emerging Spanish wines. Often their color is so dark that you can’t see the bottom of the glass, they have the smell and taste of overripe fruit, have too much alcohol and are brutally lashed with new French oak.

In my darker moments after a full day of tasting too many of these oak-whipped wines, I sometimes feel that my tongue has been trampled by the late shift at a sawmill. I wake up in a sweat, sure that one day new oak will be discovered to be a carcinogen, which would be curtains for any journeyman wine taster of this epoch.

I also get wary when I hear the claim so common with regard to Spanish wines (and others) that a special wine is exclusively from old vines. Old-vine grapes often produce superconcentrated wines that are overly rich and too much of a good thing to my palate—I have never been of the school that more is better. And I wonder, if those grapes are that good, why are they being taken out of the winery’s main blend?

Likewise, another pet peeve is the claim, also in vogue in Spain, that a wine should be unfined and unfiltered, as if those features alone guarantee wine quality. Pardon me, but I like the idea that the makers of classic Spanish wines fine their wines with fresh egg whites (as Muga, CUNE, López de Heredia, and others still do). I don’t think consumers should be straining dead lees (amply stirred by battonage these days), grape skins and other bits of debris through their teeth just so some winemaker can avoid proper racking and light filtering, if even needed after proper racking. And I am not convinced that many unfiltered wines are even stable. However, winery owners should erect a statue to whoever came up with this brilliant bit about not filtering wines. It actually allows some wineries to sell the sediment in the bottoms of their vats and barrels, thus augmenting their revenues without having to increase the amount of actual liquid they produce. But none of these trends are uniquely Spanish. To many wine lovers, it is the curse of modern wines, a curse that many of us are praying will pass.

—G.D.In the past five years in Rioja alone, scores of new wineries and new expensive modern international-style alta expresión wines have surfaced—partly in answer to a profusion of domestic challenges from international-style wines that have become media stars and partly to compete with the new generation of French “garage” wines, the boutique wine stars of California and Italy’s super Tuscans.

Back in the 1980s, when I first began visiting the Ribera del Duero, I would regularly visit several wineries—Vega Sicilia, Pesquera, Valduero, Pérez Pascuas, Balbás and Torremilanos. Now there are 140 registered wineries in the region with more on the way. It would take more than a month of nonstop work to visit them all. In Rioja, after a three-day marathon tasting called Los Grandes de La Rioja where I felt I was catching up, I still fell short. I needed at least another week just to visit the rest of the worthwhile wineries. Not to mention all of the new wines emerging from the vast wine lake of Mediterranean Spain—Alicante, Valencia, Utiel-Requena, Jumilla, Murcia, Tarragona—and the even more expansive wine region that is La Mancha and its related denominaciones de origen.

As a 30-year observer of the Spanish wine scene, nothing that the talented, industrious wine people of this vibrant country accomplish surprises me anymore. With more acreage under vine than any wine-producing country in the world, many special microclimates, some splendid terroir-driven sites that are rapidly coming to the forefront, great grapes and more accomplished winemakers, there’s no question of a remarkable future ahead for Spanish wines—and limitless enjoyment to be reached in drinking them.

First Appeared in The Wine Enthusiast, Sept. 2002

Three-star restaurants, cultish boutique wines and appreciative, affluent consumers: europe’s gastronomic epicenter just may be shifting to España.

When I first began traveling the wine roads of Spain in the early 1970s, the state of Spanish wine and food was dramatically different than it is today. Most wineries were rustic and used time-honored, often ancient, techniques to vinify grapes and age their wines. They were imbued with the romance of Old Spain and were aged in old barrels, often in moldy, cobweb-laced, ancient caves. I loved tasting them. However, while some of the wines were excellent on the spot when served with down-to-earth Spanish food like milk-fed baby lamb chops grilled over vine cuttings, air-cured hams and artisan cheeses, many of the wines were not built to travel.

Back then, there were wonderful down-home restaurants with legendary regional dishes that were often the object of gastronomic pilgrimages by Spanish aficionados. The meals included roast suckling pig and lamb, black rice paellas, fat pochas beans cooked with country chorizo and quail, and shellfish hot off a flat grill. But many ordinary restaurants were plagued with poorly trained cooks using substandard cooking oils instead of the quality Spanish olive oil that gourmands so appreciate today.

In fact, many upscale restaurants often offered so-called “continental” cuisine that seemed designed to protect foreign tourists from the horrors of olive oil, garlic and other ingredients that are now highly regarded elements of the Mediterranean diet.

In those days I often wished that the Spaniards would figure out how to get those deeply flavored, ruby-colored Duero Valley wines—in Aranda de Duero, served in earthenware pitchers—in shape to sell in foreign markets. And those wonderful Manzanilla Sherries that I drank on Sanlúcar de Barrameda’s Bajo de Guía beach at sunset with exquisite grilled langostinos (giant prawns): Would we ever be able to get fresh Manzanilla in America? And what about those deeply flawed, but incredibly promising backcountry Priorato wines I drank with grilled rabbit and allioli in the 1980s?

Up until the early 1990s, the main players in the export markets remained the well-aged red wines from Rioja, Sherries from Jerez, cheap sparkling wines from Cataluña, the wines of Miguel Torres, Sr. and the near-mythical Vega Sicilia, then Spain’s most expensive and mysterious wine. For most Americans, Spanish wines conjured up visions of a hot Mediterranean country that produced robust oak-aged reds, mediocre whites, cheap bubbly and Sherries that usually sat on restaurant and retail shelves until they were shot. Since then, there has been an explosion in the quality and breadth of Spanish wines comparable to that of California in the 1970s and 1980s. And many experts are now beginning to believe that the food in Spain these days is better than it is in any other country in Europe.

Poised on the Edge

Until the mid-1970s, the octogenarian dictator Francisco Franco was ostensibly still running the country; to outsiders, Spain seemed mired inextricably in the past. At that time, Spaniards were poised on the edge, precariously balanced between that backward post-Civil War period—an era they desperately wanted to shake—and an uncertain future, one that the many brighter lights in Spain thought was filled with promise.

During that unstable political climate, a few were willing to take a chance on the future of Spanish wine. Years earlier, Jean León, a Spanish expatriate and Los Angeles restaurateur, had already shown what could be done in Spain with estate-grown wines, producing several acclaimed Cabernet Sauvignon-based reds and Chardonnays in Penedès. In Rioja, in 1970, Henri Forner, a Bordeaux producer (Château Larose-Trintadon and Château Camensac) whose Valencian family was exiled to France during the Spanish Civil War, took the plunge and founded the Unión Viti-Vinícola, whose brand Marqués de Cáceres became a legendary success. Sherry producers such as Domecq (Marqués de Arienzo), González Byass (Beronia) and Osborne (Montecillo) either founded or purchased new bodegas in Rioja and, in 1973, Bilbao industrialist Luís Olarra founded the state-of-the-art Bodegas Olarra, one of the greatest Rioja wineries of the period.

Sherry country itself experienced something on the order of a coup d’etat as more than 50 percent of the production was gobbled up by Rumasa, a giant company with Sherry-family roots. Soon Cava country bubbled over as Rumasa moved in and took over 40 percent of the production. Building Spain’s first truly international brand of oak-aged table wines, the Torres family continued to invest profits back into their company in Vilafranca del Penedès, and year by year young Miguel Torres, Jr. made his presence increasingly felt on the style and quality of the wines. Codorníu, the Cava giant, planted a sizeable estate vineyard with Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay in Lerida province in the foothills of the Catalan Pyrenees. It then became its own denominación de origen, Costers del Segre. And, in a little-known area of the Duero Valley, Alejandro Fernández, a producer of agricultural equipment with a taste for rich, silky, but balanced and ageworthy wines, began making Pesquera, which became Spain’s first great overnight international star in the 1980s. By the mid 1990s, Álvaro Palacios (Clos Dofi and L’Ermita), Carles Pastrana (Clos de L’Obac), René Barbier (Clos Mogador) and Daphne Glorian (Clos Erasmus) had begun to put the dark, powerful wines of Priorato on the map.

Gastronomy and Winemaking Flourish

Following the death of Franco in 1975 and several more years of political turmoil, Spaniards began to excel in business, the arts, cinema, architecture, fashion and even golf. Fueled by a newly affluent and steadily expanding middle class armed with credit cards and buoyed by a surprising jump in the number of English speakers, Spain experienced an unprecedented wine and food boom that hasn’t let up. The country’s gregarious citizens who always loved to wine and dine suddenly began to take a serious interest; wine and gastronomic publications, wine clubs, wine-tasting groups and wine courses proliferated. Spaniards, like their American and European counterparts, began to see wine and food as desirable career choices; enology courses and cooking schools cropped up around the country.